As the cliché goes, Early Help is the fence at the top of the cliff, instead of the ambulance at the bottom. Instinctively that feels like common sense, but when we look at public finances we see a different picture. For example, the NHS spends 95% on the ambulance and only 5% on fencing (estimates vary between 3 and 5% spent on early intervention and prevention; figures are not published).

We’ll come back to the question of sustainable financing, for now let’s look at the evolution of early help in public services. The concept of early help or early intervention is nothing new. Health visiting started around 1862 and became a universal service in 1929, giving early advice and support to newborns and their mothers to reduce infant mortality. The term early intervention started to enter the lexicon in the 1970s. And UK legislation embraced the concept more clearly in 1997 through children’s centres and subsequently the Every Child Matters policy in 2003. A review by Graham Allen MP in 2010 took the argument forward and established the Early Intervention Foundation, which was reinforced by Professor Eileen Munro’s review of child protection which emphasised the importance of early help in the following year.

Definitions have shifted around, and for this author, the 2020 central government vision gives the best description:

Early help is the total support that improves a family’s resilience and outcomes, or reduces the chance of a problem getting worse.

Full disclosure, I was involved in drafting this definition and all the figures in this paper, and what’s important for me is how it shows the model shifting: there is no reference to services or intervention from professionals. We’re now gravitating to a more inclusive view of how outcomes are improved, which is about professionals, but also how families become more resilient in their lives, and the role of the community and environmental factors to strengthen improvement. It’s no coincidence that this change comes after a decade of austerity — as we’ll find, there is too much demand now to be met by direct intervention from public services. We need a new model.

Challenge

As previously a manager in Birmingham, I’ll give an example for the challenges we face. Ten years of cuts has drastically reduced the early help available to families. In 2019, 42% of children were growing up in poverty (think about what that means every day for a child’s lived experience). 19% of families are in households with one of mental ill-health, domestic abuse or substance misuse at an acute level. Inequality in life expectancy is between eight and ten years (and it will be much more for healthy life expectancy). And as if that wasn’t enough, the effect of Covid-19 and lockdowns was discriminatory, with a much bigger impact on the most vulnerable, compounding child, family and community inequality.

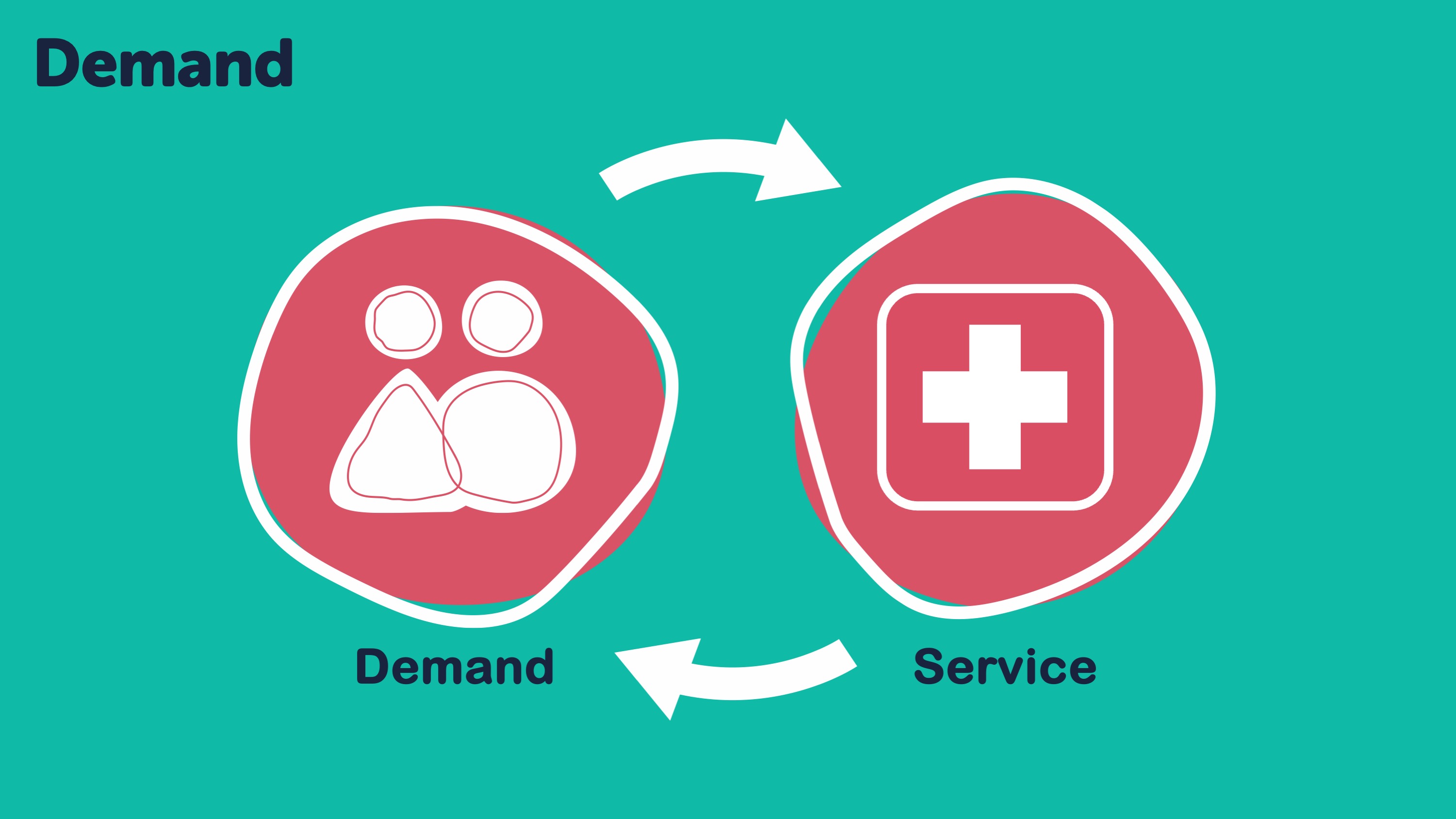

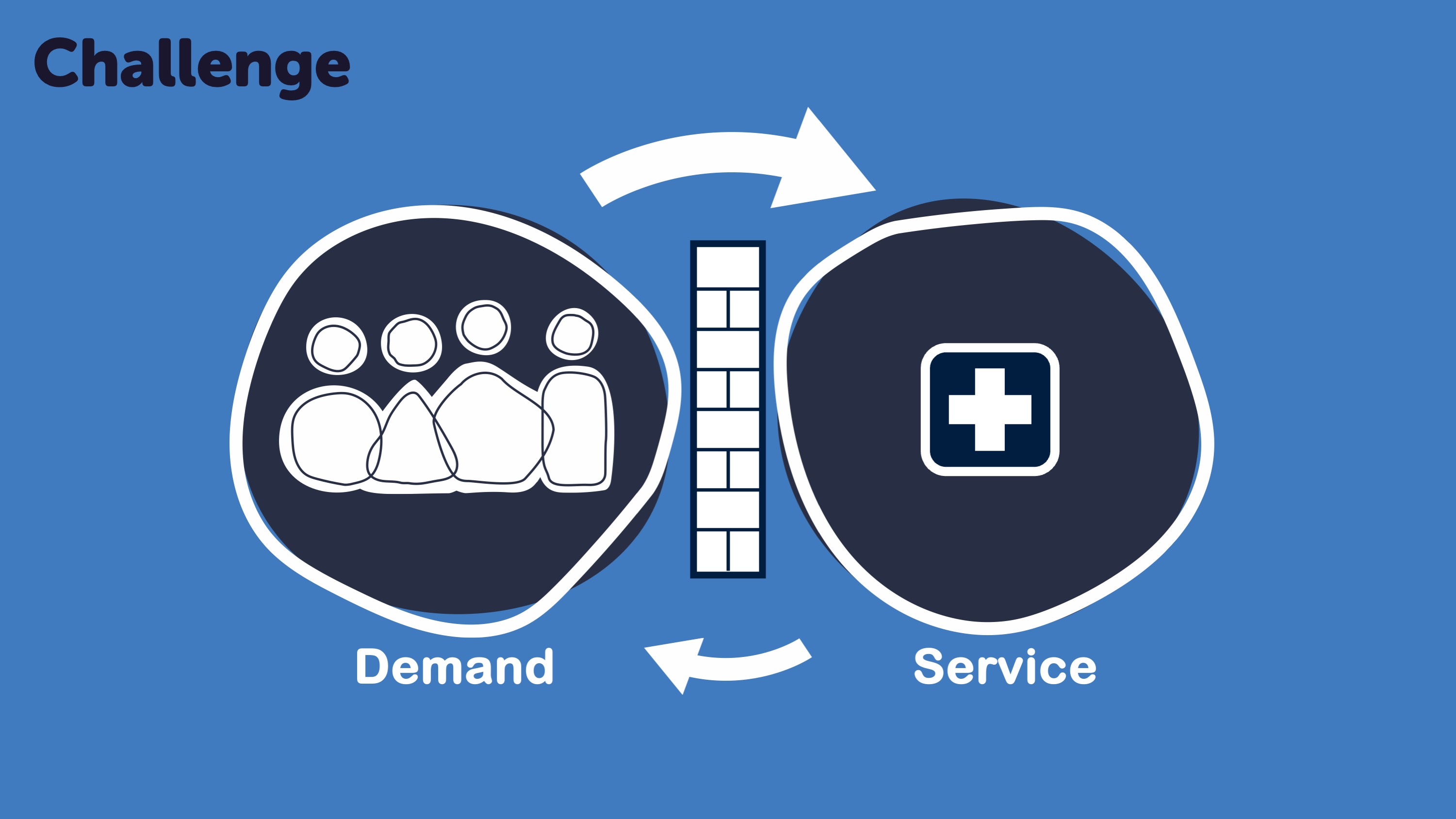

Figure 1: Simple model of how change in demand or funding leads to service rationing and waiting times

Here’s a bit of theory: Figure 1a shows a sustainable system: demand balanced with equal volume of services. And Figure 1b shows what happens when you cut the quantity of service provision:

- Fewer people are supported or treated.

- Demand builds up and we create waiting lists or higher thresholds to control demand. Thresholds are the antithesis of early help: we’re telling people they are not ill enough, come back when you are worse.

- We rationalise services, offering a lean selection with less variation and choice — a person might have need D, but we only offer service A, B or C, so they receive a service that doesn’t meet their needs.

- If you’re the person in the box, it feels unkind. It’s the author’s belief that this is a routine feeling for some people and drives a wedge between public services and the communities they serve.

This is a statutory minimum model, where cuts can and sometimes do lead to collapse. My background is in children’s services, so here are a few stats to show the hidden need for children and young people in our society:

- 2,400,000 children aged 5–16 have a mental health need or increased risk of mental ill-health. But in 2017, CAMHS received just 338,000 referrals and treated less than a third of that number. There is a huge disparity between demand and supply.

- 50% of mental health problems are established by 14-years of age but it takes on average ten years before a mental health problem starts to be treated. Evidence of a late intervention model.

- 14 times more money is spent on adult mental health than children. The funding model is the wrong way around.

Hidden need, as it’s termed, is fundamentally important for public services, because this is where the demand for acute services is generated. However, in some parts of the public sector you can observe a tendency to ignore this hidden need and create barriers to access. To be clear, I’m not exposing a commissioning conspiracy, but a subconscious behaviour of the system, driven by a necessity to ration service access because we don’t know what else to do.

It’s a bit revolutionary, but there is some new thinking in public sector design.

The only way we can reduce acute expensive demand on children and adult services, is because we are searching for and helping people in society with hidden needs. i.e. Pro-actively offering help to families, vulnerable adults, older people and their communities.

Sometimes this is called managing demand or worse, reducing demand. In reality, we want to increase demand to low-cost, targeted and much earlier support — building fences at the top of the cliff.

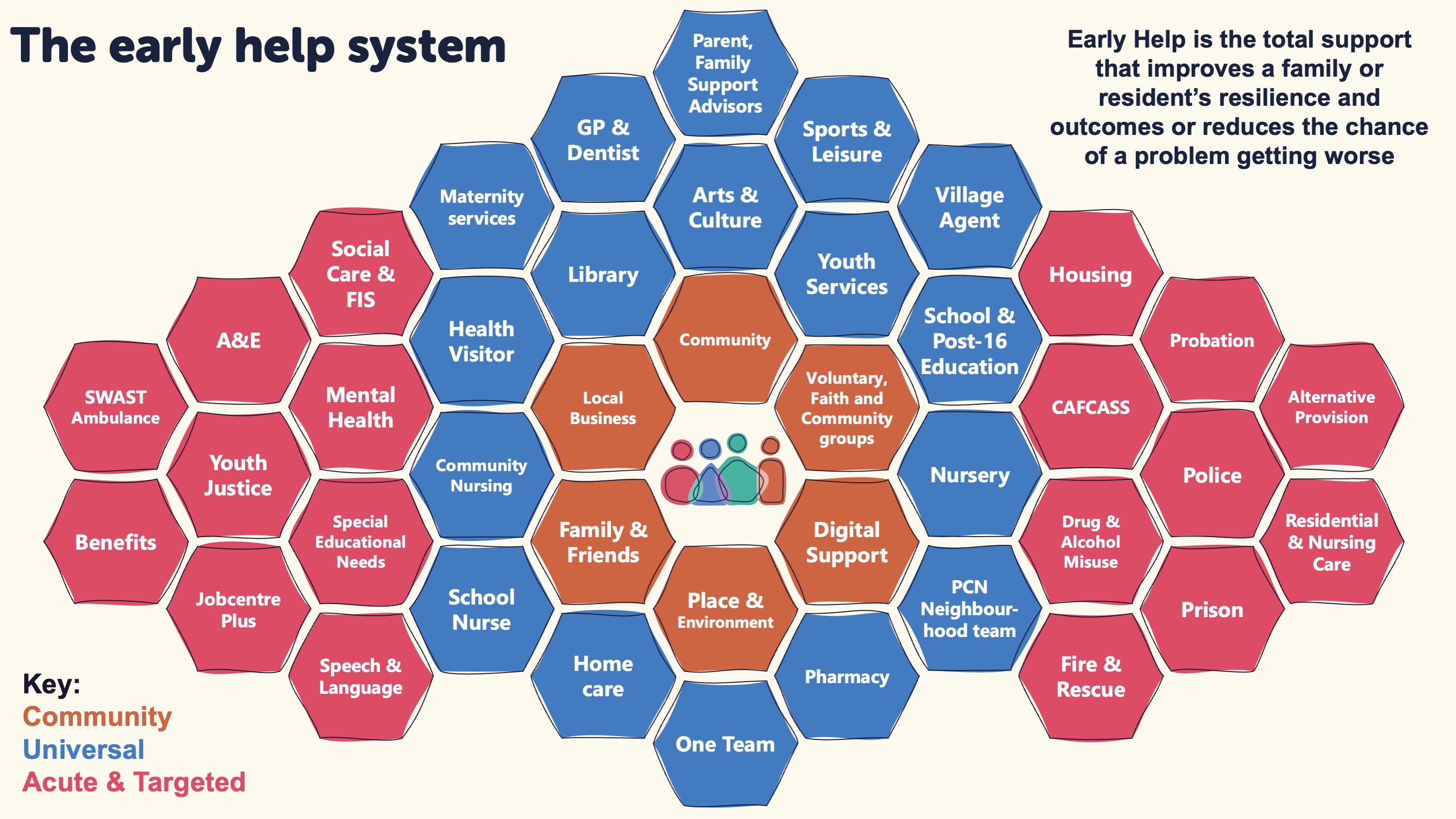

Early help system

So what does this revolutionary early help thing look like? As we talked about earlier and shown in Figure 2, the most important part is what we all personally rely on to be resilient: our family, community, faith, local voluntary or community groups (shown in green in the diagram). In blue are the universal services that are available for all children, young people and families which includes maternity, health visiting and GPs. And in pink the more specialist services that duck into early help delivery at times including mental health and A&E. In a large city like Birmingham, there might be 50,000 professionals working in this early help system, it’s a complex and sizeable resource that has a huge impact on families’ outcomes.

Figure 2: Diagram of typical services and resources contributing to the early help system.

All these services work together to some degree, and it’s the extent of the connections or integration between these services, and in-turn with community resources, that is an indicator of early help maturity. Any professional working in the early help system now needs to understand that we are not heroes rescuing a family. We are not the only line of help, or the only way to achieve outcomes. It’s about the system around each family, and therefore how we connect with other professionals and community resources to improve the lives of children and their families and increase their resilience, so they need less statutory help in the future.

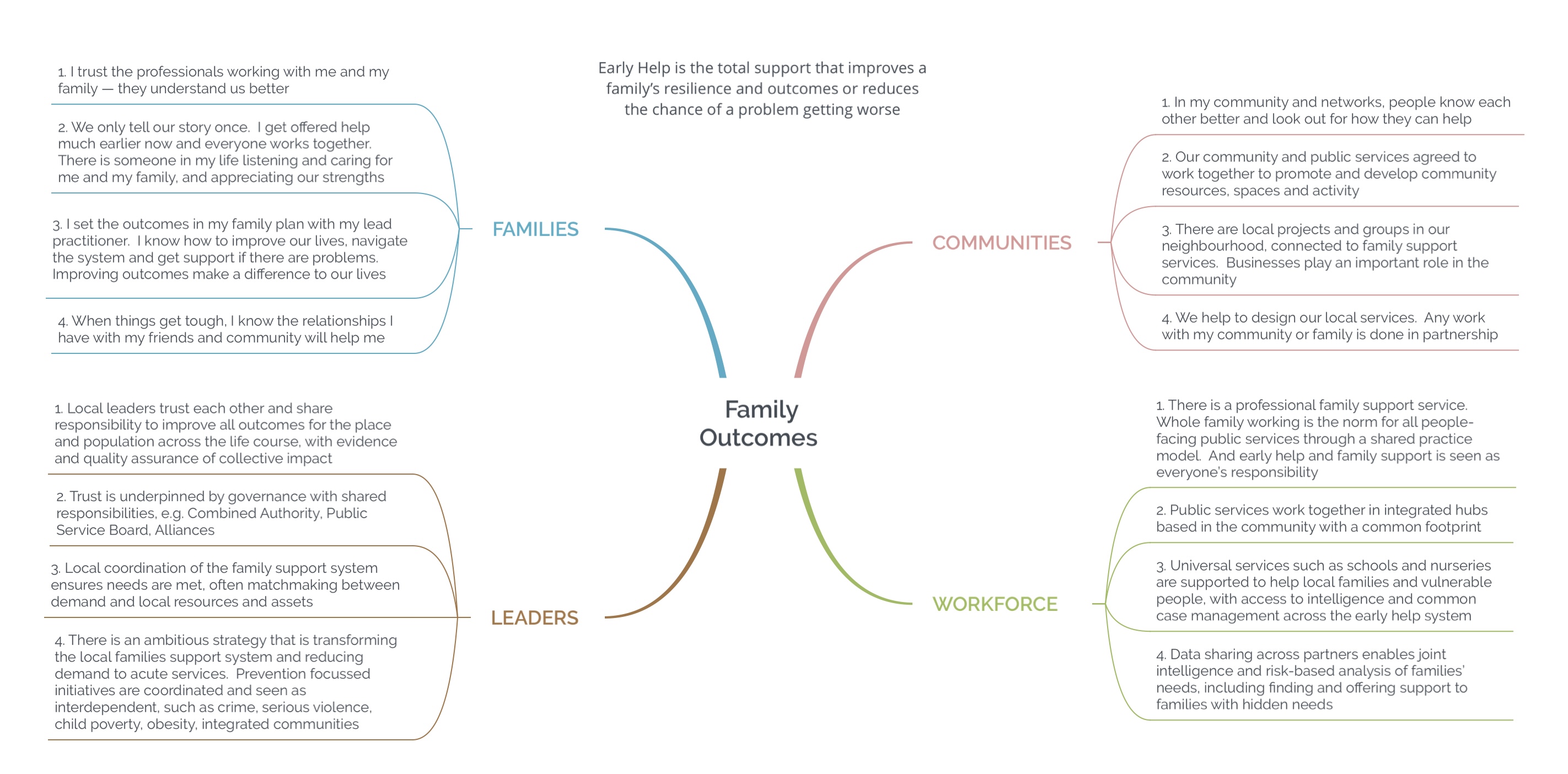

Figure 3 from central government is a little complicated, but do have a read through because it shows the main features of each part a progressive early help system: the family, community, workforce and leadership.

Figure 3: HMG vision of the early help system for children and families.

For the family, community, workforce and leaders, there is a set of expectations, connections and behaviours that makes an effective early help system. In the face of austerity, the pandemic and further austerity, many local areas are now attempting to redesign the whole early help system to be more effective, rather than improving individual services. A systems thinking, Dr Ackoff, explains why it’s so important to focus on system efficiency as well as service efficiency. His analogy of a car, is that if you took the world’s best wheels, tyre, gear box, motor, chassis etc and put it together, you wouldn’t have the world’s best car. In fact, the car wouldn’t even work. It’s the system of the components working together that make the best car.

The leadership for early help has tended to come from the local authority, but increasingly a distributed model of responsibility is emerging, and indeed there are good examples of paediatricians becoming a leading voice for progress and improvement.

Efficiency

We talked earlier about needing to support families through early help to reduce acute demand, but didn’t touch on how to do this. The trick is to make early help available to many more families.

Because of funding restraints, early help has tended to a controlled intervention model where a family receives structured support each week over maybe a six month arc. The problem is that this intervention costs in the region of £5k per family and therefore is unaffordable if we want to scale to meet all the needs in an area. What we want is a much lower transactional cost and better targeting, accepting this won’t work for everyone, but can support many more families. There are three ways to do this:

- Universal services — despite the pressures on different sectors, there is huge capacity in schools, nurseries, midwifery, health visiting and GP practices to help children and young people. To get the most out of these, we need to build confidence in their ability to support a wider range of needs with earlier identification. We can do a few practical things to enable this, and create the environment where professional connections around the family come naturally. For example, we might base professionals in local hubs and co-locate so they can build relationships with each other. We might create a team around each school or GP practice (social prescribing is a good example of enabling the connection between sectors). And we can share case records across these universal professionals, so for example, it’s easy for a teacher to pick up the phone to a friendly social worker or primary mental health worker and discuss a case and even look at the same notes. We need to reduce the barriers (we have created) to this natural and organic connection around families.

- Digital — as the pandemic showed, we can deliver a lot digitally. There are some families who are not able to access online support, but for those who are, this support can often be scaled for pennies. Online advice and guidance, parenting support and services such as Kooth are all good examples. And increasingly we will blend digital and face-to-face delivery, so a robust platform that parents, carers and young people recognise as the online place for an area is an important starting point. We also need direct communications to each parent, so we can increasingly target help.

- Community resilience — the Camden Early Help Service Manager talks about an estate where half the families are well-known to acute services. But the other half have the same needs and do not draw on services. The difference is that half the families have strong community connections, family and friend connections and resilience. What if we could help the most vulnerable people in our society to have those same connections to their communities, family and friends — would this reduce demand to expensive services? In Durham, they train teachers, nurses, social workers etc in the community resources in each locality (this is why a locality / district model is important) and how to connect families into these resources. In 90% of plans, there is now something from the community that is supporting that family’s resilience, and will continue to be there when public services step-down. Figure 4 is a bubble diagram showing how we can actively build society-wide community resilience. Finally, community hubs are important too, as a way of integrating public services to wrap more cost-effectively around families. Future paediatricians may find themselves connecting to or being part of local community hubs.

Figure 4: How community resilience can be built through local initiatives and activity.

With all public sector changes, it’s important to be able to evaluate impact so we can continue to improve efficiency and effectiveness. What’s tricky in early help is the scale of the system, and the inevitable difficulty in proving attribution of an intervention having a specific impact. The industry around evaluations has tended to steer away from evaluating whole system change programmes for this reason, instead preferring discrete programmes where the actors and recipients can be controlled.

Unfortunately, the real-world isn’t quite like this, and it’s near impossible to import a programme that’s been successful elsewhere with fidelity. Instead, in the author’s opinion, we need to be led by the evidence but not slavish to it, aware of the assumptions made through return on investment evaluations, and grow early help programmes and system-wide transformation based on local strengths. With scale and focus, it’s possible to start to see a reduction on demand to acute services in perhaps one to two years, with further benefits coming through in the longer-term.

There is another efficiency that comes from better data and analysis. The field of predictive data has huge possibilities but is still young in local government. By collecting and aggregating, with permission, more data on the lives of our residents we are able to predict how their needs are developing and offer early help at the best time to have the most impact.

If our delivery changes are about increasing the number of families that can be offered early help, then predictive analytics is able to target that resource so it has the greatest efficacy. We are able to reach out pro-actively to help families before their needs develop, for example connecting them to a local community group, asking a teacher to do something different, or providing timely advice and guidance.

Long-term, this convening or connecting of demand and resources will have a profound effect. We are moving from a world of telling people they are not ill enough to receive help, to a world where we compassionately and pro-actively look out for our citizens. There is potential, born of early help and predictive analytics, to mend the relationship between government and citizens.

Example from Birmingham

It was March 2020, Gold Command swung into action, 1000 staff redeployed, all eyes were on the Covid-19 fight. But even then, it was clear we needed to do still more for families: those that would lose their jobs, parents with mental health needs or instances of domestic abuse, the children who were unseen through lockdown.

Birmingham starts from a challenging place: 42% of our children grow up in poverty, and nearly one in five households suffer mental ill-health, domes-tic abuse or substance misuse at an acute level in any year. A decade of austerity has stripped away investment from early help: something needed to change.

We formed the Birmingham Children’s Partnership in 2019. It was based on a simple idea — to work together to tackle systemic challenges — and led by Chief Executives from the local authority, children’s trust, health commissioners and providers, the police and voluntary sector body. A small central team was set up to accelerate priori-ty projects, and as we unknowingly approached the start of the pandemic, we were forming a transformation plan and investment strategy with the ambition to have the best early help in the country.

Design

It’s obvious really, unless a city like Birmingham becomes good at catching needs early and at scale, we will always chase our tail and be forced to put the cash into late intervention. So we have an equally simple strategy:

- Significantly increase the capacity of help for families. We can’t afford to do this ourselves, so we need help in the community, in schools and other universal services, and online support to be as accessible and effective as possible. If we let go of the concept that public services are the only way of helping families, we find there are a lot of other resources that can make a huge difference and reduce demand.

- Connect our most vulnerable families to this support. For example, by training professionals in what’s in their community and how to introduce a family to a group or service. Or through widely advertising a simple list of universal early help, such as our From Birmingham with Love campaign at http://www.birmingham.gov.uk/love. We are trying to be much more proactive in search-ing out needs and offering help.

Figure 5: Birmingham Children’s Partnership offer of help for all families.

- Develop personal relationships between professionals, so they can (on first-name-terms) connect around the family without the barriers of referrals, unnecessary process and handovers. So we’ve established multi-agency teams around 500+ schools, split the city into ten localities, and are introducing a new case management system across all partners. This mirrors relational practice and co-production with families which underpins our operating model.

- Work with children and young people to develop a compelling vision. It feels easier to design the perfect ‘target operating model’ with a ‘pro-gramme management office’ and tell everyone what to do, but this approach doesn’t reflect reality. Professionals will only change because they understand the vision, it connects them to why they came into the job, and they are in-spired and empowered to improve. With more than 1000 organisations and 50,000 staff in the Birmingham early help system we had to create an authentic vision — so worked with young re-searchers and 4,000 children and young people across the city to amplify their voice and shape the vision, service design and outcome dash-board.

- Sweat the governance — we’ve made a concerted effort to improve our boards so they make a tangible difference. For early help, we’ve set up a powerful alliance with an independent chair that is underpinned by a legal section 75 pooled budget and will link into the emerging Integrated Care System structures. The Early Help Alliance has teeth: with full control as the design authority, commissioner of the ten localities, and provider of resources to each locality. New multi-agency Design Teams (including users and frontline staff) tackle the so-called wicked issues and are empowered to change our service mod-els. And we’re proud of our two transformation apprentices, with experience of our services, who are already making a fundamental impact on boards and through service design.

But don’t see our design in isolation, it’s built on the shoulders of pioneering giants and the vision of early help from MHCLG. Check out Birmingham’s local offer website for details of our vision.

Covid-19 response

Back to the pandemic, we knew families would suffer during lockdown and made some quick changes (isn’t it remarkable how fast we can move if we need to).

We were planning a year to establish ten localities (we thought this was tight) but in the end we took four weeks, with different voluntary sector organisations leading each locality. This unique model puts us more in touch with our voluntary, community, faith groups and families, enabling us to draw on community resources and connections. Health and care services are reconfiguring around the localities.

We commissioned 160 community grants and a new Community Connect service to map and then train all professionals across the system. So every-one will know what resources there are in each neighbourhood, and how to connect families we’re worried about to this support. We’ve already found 3000 more community resources.

There were still big gaps in our offer, so we quickly created new services: a personal grant scheme to help families who found themselves in a hole. This enabled our new early help teams to get a foot in the door, to understand needs and pro-actively offer more help for these families. We started to look for more needs such as contacting families in temporary accommodation and setting up support hubs in hotels. We also established a new online mental health service for quarter of a million young people in two weeks, additional mental health service capacity, online parenting support and re-designed existing services for Covid-safe delivery.

What’s the difference?

In the first year of the pandemic our new Early Help model has supported an additional 14,000 families:

- 7,400 families were assessed and supported by locality teams

- 8,000 received resilience fund grants

- 7,000 accessed new online services, and

- 8,000 received help through community grants.

It’s this scale that means we’re able to start to reduce demand to acute services. Already we’ve seen a drop in referrals to social care in comparison to other local areas.

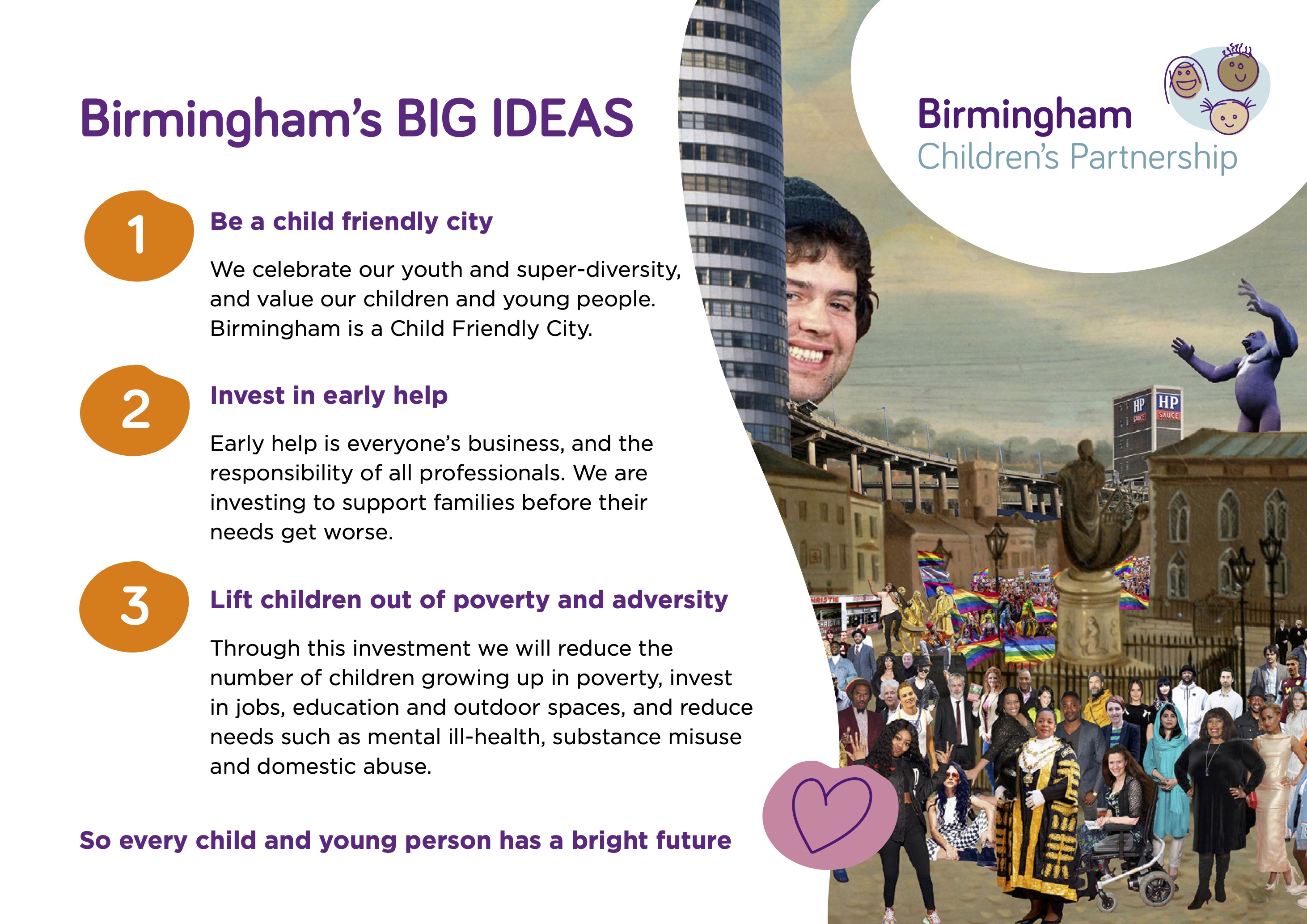

This is just the start, and we’re now galvanising the city around us to help families. We are making access to services and the localities as simple and effective as possible for partners, communities and families. And our big ideas are to:

- Be a child friendly city

- Invest in early help, and

- Lift children out of poverty and adversity.

The chief executives and services of Birmingham Children’s Partnership can’t do it alone, so we look to the city and central government to get behind our vision. This is the only way we can ensure that every child and young person will have a bright future.

Figure 6: Birmingham Children’s Partnership vision for the city, describing three big ideas that require the whole system to tackle.

References

- HM Government. Every Child Matters. www.gov.uk/government/publications/everychild-matters

- Allen G, MP. Early Intervention: The Next Steps. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/284086/early-intervention-nextsteps2.pdf

- Munro E. Munro Review of Child Protection. www.gov.uk/government/publications/munro-review-of-child-protection-finalreport-a-child-centred-system

- www.local.gov.uk/about/campaigns/brightfutures/bright-futures-camhs/child-and-adolescent-mentalhealth-and

- www.mentalhealth.org.uk/statistics/mental-health-statisticschildren-and-young-people

- www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/missedopportunities

- HM Government. Troubled Families: early help system guide. www.gov.uk/government/publications/troubled-families-early-helpsystem-guide

- Ackoff R. Systems Thinking. http://environment-ecology.com/generalsystems-theory/380-systems-thinking-with-dr-russell-ackoff.html

- ADCS. Pillars & Foundations. https://careappointments.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ADCS_Pillars_and_Foundations_Final_.pdf

- Birmingham Children’s Partnership. From Birmingham with Love. www.birmingham.gov.uk/love

- MHCLG. Building Resilient Families: Third annual report of the Troubled Families Programme 2018-19. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/790402/Troubled_Families_Programme_annual_report_2018-19.pdf

- CYPNow. Building an Early Help System. www.cypnow.co.uk/analysis/article/building-an-early-help-system

Further reading

- Birmingham Children’s Partnership. Vision for Children & Families. www.localofferbirmingham.co.uk/professionals-and-educationsettings/birmingham-childrens-partnership/birmingham-childrenspartnership-vision-for-children-and-families/

- Early Intervention Foundation. The cost of late intervention. www.eif.org.uk/report/the-cost-of-late-intervention-eif-analysis-2016

- Powell T, House of Commons Library. Early Intervention briefing paper. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7647/CBP-7647.pdf

- Selwyn R. Outcomes & Efficiency. www.amazon.co.uk/Outcomes-Efficiency-Leadership-Richard-Selwyn-ebook/dp/B007QE3LB8

This article was first published in Paediatrics and Child Health Journal, March 2022

www.paediatricsandchildhealthjournal.co.uk/article/S1751-7222(21)00206-7/abstract